Many start-up companies that focus on convenience and experience have been popularized over the past 5 – 10 years. Those that immediately come to mind include Uber, WeWork, DoorDash, and Airbnb. These companies continue to physically and psychologically change how people perceive and consume travel, food, and space.

It is no secret that many operators have entered the short-term rental (STR) market since the inception of Airbnb and similar intermediaries. A short-term rental is a furnished living space available for short periods of time, from a few days to weeks on end. Short-term rentals are also commonly known as vacation rentals and are considered an alternative to a hotel. Many operators have capitalized on a business model that produces above average returns compared with traditional 12-month rental units.

Popular STR intermediaries include Airbnb, VRBO, and Booking.com.

Interviews with national operators reveal that the expected gross income premium for utilizing a unit as an STR increases income by 2X – 3X compared with a 12-month lease in most markets.

That is, if the monthly market rent for a 12-month lease is $1,500, an STR operator can expect to attain between $3,000 and $4,500 in gross monthly rent if marketed and utilized as an STR.

These premiums, of course, will vary between markets; however, it is worth noting that my experience in the City of Lancaster suggest these numbers are very realistic and have been proven by colleagues and friends.

Unfortunately, it’s not as easy as placing the unit on Airbnb and expecting 2 – 3 times long-term rental income…gross income is just the beginning. We also must consider that owners are responsible for cleaning, coordination, and maintenance to keep the property in guest-ready condition – sometimes on a daily basis. This expense is rarely assumed by a landlord in a 12-month lease. It should also be noted that traditional 12-month renters typically pay for electric and gas expenses which are not able to be passed through when operating as an STR. Therefore, in most cases, the operational expenses for STRs are significantly higher than the expenses that would be incurred for traditional 12-month rentals.

These factors must be considered in determining the anticipated net operating income between use alternatives.

Diving deeper into expense considerations and legal permissibility of STRs in certain municipalities will be the subject of a future blog. For now, I want to focus on the valuation of STRs with the above-referenced cash flow model in mind.

In my experience, STRs in urban locales produce higher average net operating income compared with traditional 12-month rentals, all else being equal. While I understand there are many exceptions to this generalization, the balance of the blog is written from this perspective…

I have found that it is difficult for some to wrap their heads around how the STR model is so successful. And, quite frankly, that’s the reason why the STR model is so successful to those that participate in it. The perception of unstable cash flow and demanding management that is required to operate STRs translates into higher risk which keeps many seasoned investors out of the space, therefore reducing competition and putting upward pressure on daily rental rates. This phenomenon does not necessarily reduce supply, it just allows less operators to own more units – effectively allowing a few operators to “make” the market in some cases. It should be mentioned here that the real barrier to entry in STR operations and ownership is financial capacity to scale.

More units under management allows the management expense per property to be reduced to a point where an STR is more economically viable than a 12-month rental, for instance (principle of economies of scale). In essence, operators with 100 units under management can be more competitive on daily rate than operators with 5 units while still attaining the same net operating income per unit because they’ve achieved economies of scale with management expenses.

While this does not prevent a small operator from entering the STR market by any means, it is a primary reason why there is relatively low competition in the space. Therefore, if small operators cannot compete on price, they must compete on experience (think boutique hotel vs chain).

If one concludes that an STR in a given market produces higher net operating income than traditional 12-month rentals, should the property be valued as a property with a highest and best use conclusion of a short-term rental? Essentially, all else being equal, if a property exhibits that it is able to produce higher net operating income when utilized as an STR compared to its identical neighbor that’s operating as a 12-month rental, is the subject’s real estate more valuable?

To answer this question, we must acknowledge what aids in generating the rent for a short-term rental property.

The physical building is a no-brainer. STRs compete with others in their market based on physical and locational characteristics.

Furniture is next and less obvious.

How much would the daily rate for an Airbnb unit be without furniture such as beds, couches, TVs, and kitchen equipment? Probably not very much. It’s worth noting that furniture, fixtures, and equipment (FF&E) are not included in a real estate valuation.

The last component is essentially management expertise, or goodwill.

This can also be referred to as intangible value. How was the STR marketed?

Does it have 5-star reviews?

Does the operator have a “Superhost” badge?

How have they decorated?

What amenities does the unit offer (coffee, snacks, etc.)?

All of these operational factors play a role in a consumer’s decision to select a particular STR over the next.

To summarize, the daily rental rate for STR property is generated from real estate, FF&E, and intangible value. So, do the combination of these factors translate into higher real estate value?

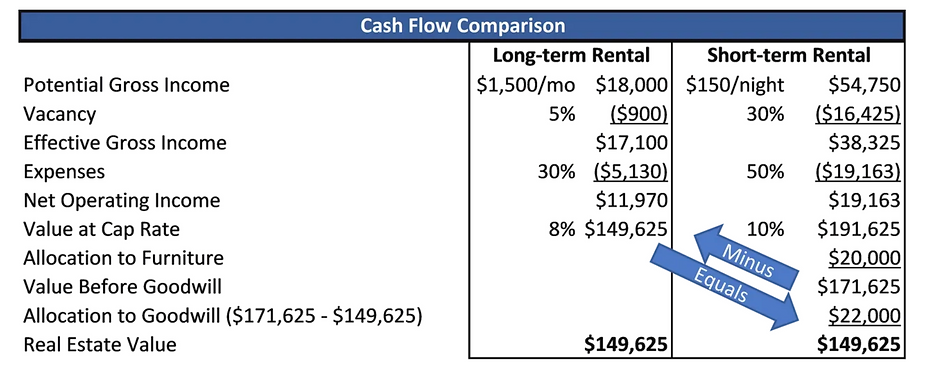

All else being equal, the net income of an STR is less stable because the income and vacancy is more variable and difficult to predict than its long-term rental counterpart. This translates into higher risk and higher investor-required yield. The following cash flow is how I would approach explaining the difference in utilizing a given unit as a short-term or long-term rental:

The underlying assumption of the above diagram is that real estate value is not increased by use of a property as an STR. My thesis is that any premium above the value a long-term rental produces is directly and entirely attributable to a combination of intangible value and furniture. This is defensible because the premium can be understood as the entrepreneurial incentive an operator assumes to utilize the rental unit in such a way. Inherently, the premium is generated from the operations and not the real estate.

Without getting too granular, the STR model is essentially identical to how a hotel operates – but it is conceptually more difficult to understand because there are multiple uses for single-family dwellings (owner-occupy, traditional 12- to 24-month rental, short-term rental) while hotels really only have one functional use…being hotels.

To attempt an analogy, consider a comparison of

1) vehicles that are utilized for food service delivery such as DoorDash, and

2) vehicles that are utilized for personal transportation.

The first is technically an income-producing tool and the next is not. All else being equal, would you pay more for the first vehicle?

Probably not.

In my opinion, this is not dissimilar to how STR valuation should be perceived relative to owner-occupied or traditional 12-month rental units.

Another analogy may be to consider two identical hotels directly next to one another.

One is Hilton-branded and the other is Marriott-branded. Hilton is able to charge a higher daily rate than Marriott because of their brand.

Does this make the Hilton-branded hotel more valuable?

As a business enterprise, yes.

But is the real estate more valuable?

I’d argue no.

In conclusion, a buyer of a property historically utilized as an STR does not enjoy the operational benefits (or weaknesses) that the seller currently realizes due to business practices specific to the seller. The question is whether or not intangible value is transferable. It’s important to remember here that when a sale occurs and operations transfer to new ownership, the reviews of operational history for the property are completely erased on intermediary sites. There are many reasons for this – the primary of which is that a review is largely contingent on cleanliness, amenities, and overall guest experience. It's rather unlikely that a new host/operator will deliver the same guest experience in the same way as a previous host. Therefore, it's difficult for me to see how an operation – deriving all or most of its guests from intermediary sites – has transferable goodwill.

Conversely, in some cases, an operator has a proprietary book of business that has been procured from past Airbnb stays (guest log at house), relationships with hospitals (traveling nurses), or corporate housing relationships. These potential guests or their representatives book directly with the operator without intermediaries. This type of STR operation likely does have transferable intangible value. Bottomline is that the transferability – or existence – of intangible value is highly dependent on how the income is being generated. If it has been determined that intangible value is present in the operations, it’s important to recognize that this is ancillary and completely distinct from the real estate. Therefore, it is my opinion that the premium derived from operating as an STR should not be included in a real estate market value appraisal.

I’m not maintaining that STR properties cannot be sold for a premium over traditional 12-month rentals – I acknowledge that they can be. I’m maintaining that the premium is not generated by real estate characteristics, rather operational characteristics. Therefore, the premium should not be included in a real estate market value appraisal.

Whether a buyer wants to pay for the difference in cash to acquire the business and furniture is their choice; however, it is misleading to point to transactions that have occurred whereby the buyers did not allocate between real estate, furniture, and intangible value as defense. Although sales of STRs have and do occur this way, it’s my opinion that transactions occurring this way are a result of convenience and ignorance rather than appropriate valuation technique. I am simply contending that it is misleading, incorrect, and a result of groupthink to describe an STR acquisition – based on its historical income generating capability – a real estate transaction only.

This type of transaction includes real estate, furniture, and [in some cases] intangible value and should be treated as such.

Similar to essentially all other aspects of real estate valuation, I expect the debate on how to appraise an STR will continue with no real consensus.

A wise man once said, “Differences of opinion make the market.”

These are simply my opinions; do with them what you will.

I’m sure there are good and fair counterarguments and I welcome them.

The fact is this property type is not going away – especially with supply constraints and high investor demand.

Disclaimer: If interested in operating an STR, please consider consulting with the local jurisdiction in which the property is located. Local ordinances are a critical consideration. Each city or county defines differently what qualifies as a short-term rental property, and the fees are hefty for homeowners who rent illegally. Owners and prospective owners should verify local regulations, zoning, taxes, and licensing before utilizing their property as a short-term rental.

Michael J. Rohm, MAI, CCIM, R/W-AC, is a fee appraiser and real estate agent working throughout Pennsylvania.

He is the Founder and a Partner at Commonwealth Commercial Appraisal Group and is Director of Valuation Advisory

and Senior Associate with Landmark Commercial Realty.

Like this blog? Share it!